AMAZON WATCH MARCH 2002

Report On:

Civil Conflict and Indigenous Peoples in Colombia en español

After forty years of civil war, Colombia is sliding ever deeper into conflict. The recent collapse of the peace process has set a new wave of violence in motion. The brutal tactics of paramilitary groups, leftist guerillas, security forces, and drug traffickers result in the violent deaths of almost 20 Colombians every day. At least 2 million Colombians have been displaced since 1985 and nearly 300,000 per year in recent years. A striking characteristic of Colombia's conflict is that most victims of war are unarmed civilians -rural villagers, small farmers and civil society leaders.

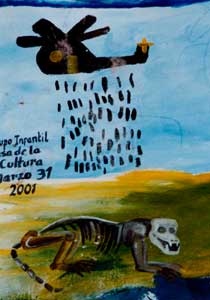

"Mural in La Hormiga" Photo credit: Phillip Cryan

Living in remote areas effectively abandoned by the state, indigenous peoples are among the most vulnerable in Colombia. The US Department of State's 2001 Report on Human Rights Practices for Colombia states, "indigenous communities suffer disproportionately from the internal armed conflict". The location of much of the nation's natural resources beneath indigenous ancestral lands has turned indigenous communities into targets for abuses and forced displacement. Their peaceful struggle for territorial and cultural rights and their alternative vision of community development pits indigenous peoples against the powerful economic interests fueling the war.

Living in remote areas effectively abandoned by the state, indigenous peoples are among the most vulnerable in Colombia. The US Department of State's 2001 Report on Human Rights Practices for Colombia states, "indigenous communities suffer disproportionately from the internal armed conflict". The location of much of the nation's natural resources beneath indigenous ancestral lands has turned indigenous communities into targets for abuses and forced displacement. Their peaceful struggle for territorial and cultural rights and their alternative vision of community development pits indigenous peoples against the powerful economic interests fueling the war.

As this report will demonstrate, indigenous peoples are being pushed to the brink by damages from crop fumigation and the intensification of civil conflict resulting from the Colombian government initiative, Plan Colombia, substantially funded by the United States. Many indigenous rights abuse cases cited in this report occurred after the commencement of Plan Colombia. In the words of Roberto Perez, President of the U'wa Traditional Authority:

"Plan Colombia is a death sentence for us . . . [It] is a plan for violence. The money the United States is spending in Plan Colombia will go to protecting the international companies by purchasing arms, more sophisticated equipment, and to constructing military bases in the richest [resource] zones. And when they say they will eradicate the coca crops by aerial fumigation, they are contaminating the environment, the rivers, and the [agricultural] cultivations that is for local subsistence" (Feb 7, 2001).

Recent shifts in US policy have placed Colombia on the agenda of the Bush administration's global counter-terrorism initiative. The redefinition of US aid strategy has formulated proposals to support the Colombian military not only in counter-narcotics exercises but also in counter-insurgency operations. President Bush has for the first time openly stated that some military aid should be used to protect US economic interests in the region, specifically the Caño Limon oil pipeline part owned by the US oil company Occidental Petroleum (OXY).

The deepening involvement of the United States in counter-insurgency efforts and the protection of energy infrastructure bodes ill for the many indigenous communities living on top of or near the region's energy resources. The expanding US role in Colombia's civil war will lead to the intensification and extension of violent conflict in Colombia's indigenous communities.

Colombia's Indigenous Peoples

Considering its small size relative to the national population, Colombia's approximately 800,000 strong indigenous population is strikingly diverse. 84 indigenous peoples speaking 64 different languages live throughout Colombia's distinct geographical regions covering more than 50 million acres of titled land.1

'The Indigenous Movement in Colombia', Jesus Avirama and Rayda Marquez. In Indigenous Peoples and Democracy in Latin America, Donna Lee Van Cott (ed.), Macmillan Press, 1994.

In Colombia, as in the rest of Latin America, indigenous peoples live with a colonial legacy of land loss, socio-economic marginalization, racial and ethic discrimination and human rights abuses.

To cast off this legacy, Colombia's first indigenous organizations were formed in the 1970s. Organizations such as ONIC (National Organization of Colombian Indigenous Peoples) have fought for cultural rights, land recuperation, community development and institutional participation. By the 1990s, indigenous leaders had won sufficient political leverage to play a pivotal role in writing Colombia's new 1991 constitution, which incorporated substantive recognition of indigenous cultural, territorial and political rights.2

Ibid.

By 1996, 80% of the indigenous population was living on titled communal lands (resguardos) covering 25% of the national territory. 73% of these lands are in the Amazon region.

Just as the indigenous struggle was finally bearing fruit, a combination of global economic forces, mounting civil conflict and increasingly virulent armed groups plunged Colombia into crisis. With state authority and national democracy undermined by weak governmental institutions and pervasive corruption, armed sectors of Colombian society intensified their fight for control of the country's rich natural resources.

Adamantly voicing their own neutrality, indigenous organizations insist on the right of indigenous peoples to remain autonomous from Colombia's political maelstrom. Yet escalating civil war has increasingly placed indigenous communities in the crossfire between warring factions. Ignoring the neutral stance of indigenous peoples, armed groups frequently accuse indigenous leaders and communities of political partiality, making them 'legitimate' targets for violence. As Cauca indigenous leader Gerardo Delgado stated,

"They (indigenous peoples) get kicked by both the right and left military boots".

So many indigenous leaders have now been assassinated that indigenous organizations are barely able to function in many parts of Colombia. In June 2001 the Latin American Association for Human Rights estimated that half of Colombia's indigenous peoples face annihilation from encroaching violence. Factors such as land invasion, oil operations and mega-development projects also increase their vulnerability. One example is the case of the Karijonas from the southeast whose numbers have dropped to 70, from 280 in 1993.3

'Colombian Tribe Is Threatened by an Encroaching Civil War', Juan Forero, May 14, 2001.

U.S. Military Aid

In 2000, President Clinton approved a $1.3 billion aid package to Colombia principally for training and equipment for Colombia's army. Though President Pastrana originally pitched Plan Colombia as an effort to strength the peace process and boost economic development, with U.S. aid, the Plan became a predominantly military initiative to eradicate drug trafficking.

In March 2001, President Bush announced his own 'counter drugs' strategy for 2002, the Andean Regional Initiative. Pitched by Bush as a 'balanced package' of military and socio-economic spending, this initiative cut military and police aid for Colombia by an estimated 24 percent in 2002 from 2000-2001 levels, but increased military aid to other Andean nations. The militarization of the entire Andean region is the expected result of large increases in military aid for Colombia's neighbors. Bush's new $880 million initiative comes in addition to the $1.3 billion two-year package approved in 2000.4

'US military and police aid: The 2002 aid request', Center for International Policy, May 2001

Senate amendments to the Andean Regional Initiative did strengthen human rights conditions but there has been no improvement in human rights abuses on the ground. 5

'Senate Votes on Colombia Package; Bill Goes to Conference Committee; Act Now!', Latin America Working Group, November 2001. 'Foreign Operations Bill Stuck in Conference Committee', Latin America Working Group, December 2001.

The following evidence underlines the failure of the US aid to accomplish stated aims. Yet, recently announced proposals would broaden the scope of US policy to allow aid to be used for counter-insurgency operations and the protection of economic infrastructure. It is proposed that all past counter-narcotics aid to Colombia be used in a unified campaign against narcotics trafficking, terrorist activities, and other threats to [Colombia's] national security. In addition, President Bush recently requested that US$98 million be used to increase security for the frequently bombed Caño Limon oil pipeline operated by US-based company Occidental Petroleum.

Human Rights Abuses Increase

Since Plan Colombia, critics have argued that U.S. promotion of military responses to civil war has actively contributed to the current escalation of violence and dealt a blow to civil society organizations working for peaceful solutions to conflict. Since U.S. aid arrived in the region, massacres have multiplied largely as a result of the burgeoning power of various paramilitary groups, some of which are part of the umbrella organization, the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC). The number of massacres in the first four months of 2001 is roughly double the figure for the same period in 2000. ONIC reported that 35 members of indigenous organizations were killed between January and July 2001. The Colombian army has rarely acted to protect the civilian population even in the numerous cases in which pleas for help are issued prior to attacks. 6

'July 2001 Update on Main Actors in the Colombian Conflict', Washington Office on Latin America.

Military Ties to Paramilitaries Continue

U.S. refusal to attach adequate human rights conditions to military aid has covertly sanctioned military and related paramilitary human rights abuses. The Colombian military has the worst human rights record in the hemisphere. The Colombian government's Social Solidarity Network reported in April 2001 that paramilitaries had killed 529 of the 769 people that died during massacres in the first four months of 2001. 7

'Colombia killings rise, government blames militias', Reuters, April 18, 2001.

Yet, both tacit and active military collaboration with paramilitary groups is well documented. 8

'Colombia Human Rights Certification II', Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA), January 2001; 'Colombia Human Rights Certification III', Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA), February, 2002.

Amnesty International reports that military inaction is the principle factor behind the failure to enforce the majority of the arrest warrants issued by the Attorney General against paramilitaries. 9

Amnesty International Colombia Country Report 2001.

A February 2002 report by major human rights groups shows that, despite the US condition that the military make progress to sever ties to paramilitaries, the Colombian military continues to aid and abet paramilitary groups through the provision of intelligence information and equipment and through not defending civilians from paramilitary attacks. Yet, recent changes to US policy have led President Bush to call for an end to the already limited human rights conditions attached to military aid.

"Fumigated Corn Field in El Placer" Photo credit: Phillip Cryan

Fumigation Fails

Fumigation Fails

US contributions to Plan Colombia also initiated a sustained program of aerial eradication of illegal coca and poppy crops using harmful herbicides. Aerial spraying has damaged the environment, destroyed food crops, and forced many Colombian farmers to flee their land and livelihood. The U.S. aid package originally stipulated that alternative development programs would accompany fumigation. Yet, a lack of governmental coordination has resulted in fumigation wiping out local sources of food and income while USAID development programs are struggling to get off the ground and blanket spraying is seriously undermining the viability of voluntary eradication pacts. 10

Outlining discrepancies in the U.S. aid package, Senator Leahy (D-VT) made the case in the Senate in fall 2001 that crop eradication is not a solution to drug trafficking. Since fumigation began there has been no fall in U.S. demand and, according to 2002 US government figures, the expanse of coca fields in Colombia has increased by 25%.

Coca and Indigenous Peoples

Why Farmers Grow Coca

For indigenous peoples, coca is a sacred plant used for ritual and medicinal purposes for thousands of years. The mass production of coca and associated drug abuse are contrary to traditional indigenous social and cosmological practices. Yet, various factors push indigenous communities to cultivate an estimated 17% of Colombia's illegal crops. 11 11

Critics argue that U.S. funded policies to eradicate illegal crop cultivation through aerial fumigation ignore the rationale driving small farmers to produce drug crops. Profitable lawful economic activities are scarce in violent frontier areas with little basic infrastructure and services and few market links to the national economy.12

Violence is at the core of coca production. Armed factions that kill unarmed civilians with impunity exhort communities to plant coca and then buy their coca paste directly at artificially low prices.14

Coca Devastates the Cofán

The Cofán peoples of southeastern Colombia were forced into coca production to survive, both physically and economically. In the 1980s the spread of the coca industry into their homelands caused untold damage. Colonizers who cut down forests and took possession of Cofán lands to grow coca, inundated the region. Conflict over land ownership resulted in the death of Cofán community members. Those Cofán who would not grow coca were forced to flee the region. Intimidated by armed groups, the bulk of their productive lands stolen and their fish and game supplies reduced, those that remained had little option but to plant coca.

For the Cofán, illegal crop cultivation led to the breakdown of traditional ways of life due to social and economic disruption, deforestation, loss of ancestral lands, violence and criminality. 15

However, displaced Cofan are again under threat. With coca production spreading into Ecuador both guerilla and paramilitary groups are expanding their activities over the border. In February 2002, armed paramilitaries operating in Sucumbios, Ecuador forced the inhabitants of 6 Cofan and Quichua indigenous communities to abandon their homes, lands, crops and animals under the threat of death. 17

Impacts of Fumigation

Firstly devastated by coca production, the Cofán and other indigenous and rural communities of southeastern Colombia are now suffering the impacts of government attempts at  coca eradication. Indigenous communities of the region have been affected disproportionately by crop fumigation practices involving the aerial spraying of the herbicide Roundup Ultra.

coca eradication. Indigenous communities of the region have been affected disproportionately by crop fumigation practices involving the aerial spraying of the herbicide Roundup Ultra.

The St. Louis-based chemical and biotechnology giant, Monsanto who manufactured Agent Orange, a controversial defoliant used during the Vietnam War, is also the maker of Roundup, Ultra. Roundup's active ingredient, glyphosate, was ranked third out of 25 chemicals harmful to humans in a 1993 EPA study.

According to a CorpWatch report, an estimated 70,000 gallons of Roundup Ultra have been sprayed in Colombia in the first six months of 2001. In 2000, roughly 145,750 gallons were sprayed covering over 131,000 acres. 18

Fumigated Corn in El Placer" Photo credit: Phillip Cryan

U.S. private aircraft companies and the Colombian air force spray this lethal chemical over the region's impoverished villages and farms contaminating drinking water sources, destroying food crops and poisoning and killing livestock. Observers report that aerial spraying is conducted from too high of an altitude to accurately target the drug crops; hence many subsistence crops and bodies of water are contaminated. In November 2000, 10 successive days of aerial spraying over Inga indigenous reserves in Nariño left 80 per cent of children ill. A local doctor spoke of an epidemic of fever, diarrhea and severe skin and eye complaints. 19

A Colombian agronomist, Elsa Nivia, has stated that in the first two months of 2001 alone, local authorities reported 4,289 humans suffering skin or gastric disorders, while 178,377 creatures, including cattle, horses, pigs, dogs, ducks, hens and fish, were killed by the spraying. 20

Even Monsanto labels warn about toxicity: "Roundup will kill almost any green plant that is actively growing. Roundup should not be applied to bodies of water such as ponds, lakes or streams as Roundup can be harmful to certain aquatic organisms." Labels goes on to recommend that animals should stay out of treated areas for two weeks and that in the case that fruits or nuts from trees have been sprayed, these should not be consumed for twenty-one days. Even so, the US State Department denies Roundup Ultra is harmful.

Recent evidence suggests that the health impacts of the aerial spraying in Colombia may be related to the use the additive Cosmo Flux 411F, a surfactant to Roundup Ultra. In May 2001, Dr. Nivia said: "the [Roundup Ultra] mixture with the Cosmo Flux 411 F surfactant can increase the herbicide's biological action fourfold, producing relative exposure levels which are 104 times higher than the recommended doses for normal agricultural applications in the United States; doses which, according to the study mentioned, can intoxicate and even kill ruminants." Authorities acknowledge that the mixture has not been fully tested.

The disproportionate impact of fumigation on indigenous peoples led the Organization of Indigenous Peoples of the Colombian Amazon (OPIAC), with support from the Colombian government's own Human Rights Ombudsman's Office, to take legal action calling for a ban on aerial spraying in indigenous territories. An initial court ruling suspended fumigations in July 2001 but was overturned shortly thereafter.21

The Rural Status Quo

A History of Conflict

The conflict of interests between indigenous communities and Colombia's rural elite dates back centuries. In Colombia land tenure is concentrated in the hands of large agriculturalists and the private sector is in control of almost all agricultural investment. Consequently, small farmers struggle for survival in the shadow of large landowners.22

The Rights Of Indigenous People In Colombia, Second Report On The Situation Of Human Rights In Colombia, InterAmerican Commission of Human Rights, 1998.

The considerable economic power of elite producer groups is matched by their potent political influence at all levels of government. 23

'Alternative Development Won't End Colombia's War', Jason Thor Hagen, Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy, 2001.

In asserting their historical claim to ancestral land rights, indigenous communities subsequently challenge the rural status quo. Since colonial times, rural elite have traditionally perceived indigenous territorial demands to be an attack on the economic and political foundations of their own power.

Hostilities in rural Colombia worsened after neoliberal economic reforms of the 1990s plunged Colombian agriculture into a profound slump. The elimination of protective cover for agricultural products compelled Colombian agriculturalists to compete in a global environment. Obliged to redirect agricultural production, Colombia's landowning elite fought to acquire yet more lands for profitable livestock production. Intensive competition for land turned resentful eyes towards the indigenous communal land base.

Paramilitary Attacks

Among Colombia's large landowners are drug barons who launder profits by buying up vast expanses of land mainly in coastal regions. Drug barons, as well as the traditional landowning elite, have a history of hiring private armies to protect their economic and political interests. Today, these paramilitary groups use selective assassinations, forced disappearances, massacres, and forced displacement of entire populations to control poor farmers, rural villagers and indigenous communities standing in the way of their interests.24

'Information about the Combatants', Center for International Policy, November 2001.

Large landowners eyeing indigenous lands often fund paramilitary terror campaigns to forcibly displace communities. The department of El Cauca has one of the highest concentrations of indigenous people in the nation, made up of Paez, Yanagona, Coconuco and Guambiano communities. The entrenched interests of the agro-industrial sector in El Cauca are reflected in the particularly high levels of abuse and displacement among indigenous peoples. 25

The Rights Of Indigenous People In Colombia, Second Report On The Situation Of Human Rights In Colombia, InterAmerican Commission of Human Rights, 1998.

A recent Amnesty International delegation to El Cauca reported that Naya River indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities exist under constant threat of violent attacks from paramilitary groups. In April 2001, paramilitaries massacred 35 people in the Naya Valley and ordered remaining communities to abandon their lands. 26

'Colombia: Las comunidades del Cauca quedan en el desamparo', Amnistía Internacional Comunicado De Prensa, 8 August, 2001.

Frequently, agricultural enterprises move in on deserted lands.

In the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, paramilitaries are using a different strategy against the Wiwa and Koggi indigenous population. Instead of forcing communities to flee their lands, paramilitaries are using violent intimidation to wipe out community organizing efforts including mothers' meetings and children's meal programs. Landowners funded the expansion of paramilitaries into the region in Spring 2001 after a wave of guerilla kidnappings of wealthy ranchers.27

"The indigenous communities are considered a military objective by all the armed groups not for belonging to any one side, nor having connections, but rather for defending our position."

Government passivity in the face of paramilitary violence gainsays official recognition of indigenous rights. As a Caldas indigenous leader recently commented, " we are tired of meeting with government officials and listening to their promises and then returning to our communities to see the same river of blood."

Guerrilla Abuses

Colombia's Armed Revolutionary Front (FARC) and National Liberation Army (ELN) have repeatedly committed violations of human rights in indigenous communities. In Cauca, FARC is believed to be responsible for the death of four indigenous peoples in December 2000. Governor Floro Alberto Tunubalá of Cauca, Colombia's first indigenous governor, and his cabinet have received threats from both the paramilitaries and FARC.28

'NGO Declaration Against Violence in Cauca and in Solidarity with March Against the Violence', May 17, 2001.

In January 2001, FARC guerillas killed an indigenous mayor from Chocó who represented the Indigenous Social Alliance and had criticized the earlier murder of fellow indigenous leader Armando Achita. 29

US Department of State 2001 Report on Human Rights Practices for Colombia.

Forced recruitment of indigenous children by the FARC has traumatized indigenous families. The Arhuaco people of the Sierra Nevada have been powerless to resist FARC groups invading their villages to buy provisions and to forcibly recruit teenagers. The Arhauco know that although recruitment is forced upon them, paramilitary groups will accuse them of collaborating with rebels as in the case of their neighbors, the Kankuamus people, who were killed by the dozens and relocated to shantytowns by paramilitaries. 30

'Colombian Tribe Is Threatened by an Encroaching Civil War', Juan Forero, May 14, 2001.

Strategic Economics

The Indigenous Plan for Life

Colombia's 1991 constitution granted legally recognized indigenous 'resguardos' (reserves) the right to autonomous economic and social development. Many indigenous peoples seized this opportunity to establish their own community development programs, known as 'Plans for Life' grounded in indigenous communal interests and cultural values. For example, in 1994, the Guambiano people of Cauca developed a 'Plan for Life' based in an inclusive, community-based vision of development that would eradicate socio-economic inequality and discriminatory social structures. 31

'Plan de Vida - an Indigenous Initiative for Cultural Survival', Bastian Hermisson, Cultural Survival Quarterly 23 (4).

Indigenous community values directly contradict capitalist economic models based on notions of private property and individual enrichment. Not surprisingly, Colombia's corporate elite often does not take a favorable view of indigenous efforts to take control of economic development in their homelands. Approximately 95 percent of the region's natural resources are found on legally titled indigenous lands and areas claimed by indigenous peoples as ancestral territories. Sitting on top of rich natural resources and resistant to large-scale development projects, indigenous communities are viewed as an 'obstacle' to 'progress'. Whenever convenient, corporations and large landholders accuse indigenous communities of being guerilla sympathizers or being manipulated by guerillas.

Development Mega-Projects

The case of the Embera Katío people of Cordoba illustrates the consequences for indigenous communities of resisting large-scale development projects on their lands. The Embera Katio engaged in a lengthy legal struggle for compensation for the environmental and social impacts of the Urra hydroelectric dam constructed near their land. The final judgment ordered an Embera compensation and mitigation plan.

As a direct response to Embera resistance to the dam, paramilitary forces entered the Embera Katío reserve bringing a wave of murders, disappearances, and intimidation of community leaders.32

'Colombian Paramilitaries Suspected of Murders of Four Indigenous Leaders and 21 Abductions', International Rivers Network, October 8, 2000.

The paramilitary forces attempted to force the Embera peoples to grow coca, which the Embera have always prohibited. The farming communities just outside the borders of the reserve were massacred and forced to flee. The Embera peoples have chosen not to flee. Community leaders also refuse to allow guerilla enclaves or activities on their lands, leading to frictions with guerilla groups. The persecution of Embera leaders reached a peak in Summer 2001. After the abduction of high profile Embera leader Kimi Pernia Domico, Pedro Alirio Domico, the reserve governor, was murdered by paramilitaries for protesting Pernia's disappearance. 33

'Urgent Action Appeal', Amnesty International, June 27, 2001.

The U.S. Oil Industry and Military Aid

Instability in the Middle East is sharpening the US government's demand for increased Latin American oil production. Critics argue that President Bush's recent request for US$98 million to protect the Caño Limon oil pipeline in illustrative of Colombia's growing strategic significance within US energy policy.

'Military breaks up peaceful U'wa blockade'

U.S. oil companies have lobbied heavily for U.S. military aid to Colombia. Testifying in support of Plan Colombia, an Occidental Petroleum representative argued that the Colombian military was "vastly under-armed." Critics of military aid argue that its real aim is to remove threats to U.S. economic interests in the region. The Rand Corporation, a conservative think tank with great influence on U.S. foreign policy, stressed in a 2001 report commissioned by the U.S. Air Force, that Plan Colombia must solidify U.S. hegemony in Colombia before civil war prevents access to the region's immense oil reserves. 34

U.S. oil companies have lobbied heavily for U.S. military aid to Colombia. Testifying in support of Plan Colombia, an Occidental Petroleum representative argued that the Colombian military was "vastly under-armed." Critics of military aid argue that its real aim is to remove threats to U.S. economic interests in the region. The Rand Corporation, a conservative think tank with great influence on U.S. foreign policy, stressed in a 2001 report commissioned by the U.S. Air Force, that Plan Colombia must solidify U.S. hegemony in Colombia before civil war prevents access to the region's immense oil reserves. 34

'Colombian Labyrinth: the Synergy of Drugs and Insurgency and Its Implications for Regional Stability', Angel Rabasa and Peter Chalk, RAND, 2001.

US government backing for US oil interests in Colombia has severe implications for indigenous peoples. Preliminary documentation of indigenous displacement in a forthcoming report by ONIC and the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) indicates that in many cases displacement is driven by the desire of armed groups to access natural resources such as coal, oil and gold. The forced removal by paramilitaries of approximately 400 indigenous people from the Caño Limon pipeline region of Norte de Santander in February 2001 is an illustrative case.35

'Military breaks up peaceful U'wa blockade'  Oil and Militarization

Oil and Militarization

Indigenous peoples such as the U'wa people of northeastern Colombia have already come up against U.S. oil interests in Colombia. The U'wa people's struggle against the U.S. oil giant Occidental Petroleum (OXY) demonstrates the link between oil, violence and US military aid. To protect its operations, OXY relies heavily on Colombian security forces. Oil companies working in Colombia must pay $1 on every barrel of oil produced, which goes directly to the military for its protection services. One in four Colombian soldiers are currently devoted to protecting oil installations. During early 2001, up to 3,000 Colombian soldiers occupied U'wa lands in the name of defending oil drilling machinery and sites. On several occasions, violent police crackdowns on peaceful road blockades by U'wa people and supporters left many injured and three indigenous children dead. Three American humanitarians working with the U'wa were kidnapped and executed by guerillas.

Human rights and environmental groups have highlighted the connection between oil development and militarization for years. Both guerilla and paramilitary groups are attracted to oil producing areas by the opportunity to acquire oil revenues from corrupt and/or fearful local officials and 'war taxes' from oil companies. OXY's Vice President of Public Affairs has testified before Congress that employees are "regularly shaken down" by both the FARC and ELN guerilla groups who demand payment in return for permitting oil operations.

The 1998 Santo Domingo air attack in Arauca testifies to the direct involvement of security companies hired by US oil corporations in civilian killings. AirScan, a private airborne surveillance firm contracted by OXY to protect the Caño Limon pipeline, provided strategic information for military counter-insurgency offensives. Testimony from military officers affirms that for the Santo Domingo attack, AirScan used airborne equipment to pinpoint ground targets for bombing. Moreover, OXY's oil installations were used as the launching ground for the attack, which was planned and initiated at company headquarters using the company air strip. The attack killed 18 civilians, including nine children. No rebels died. This case is under investigation by the Colombian courts.36

'U.S. Pilots Summoned in Colombian Bombing Probe', Phil Stewart, Reuters, June 14, 2001.

However, armed men who, according to local human rights groups, were allowed to pass through a military roadblock in the area assassinated a key witness in the case in January 2002. 37

A Colombian Town Caught in a Cross-Fire. The bombing of Santo Domingo shows how messy U.S. involvement in the Latin American drug war can be. T. Christian Miller, Los Angeles Times, March 17, 2002.

Indigenous communities located in areas of U.S. strategic oil interests have witnessed the militarization of their ancestral homelands. During Summer 2001, paramilitary groups began to surround the U'wa region. A string of brutal massacres in neighboring Arauca has terrorized the local population. 38

'Paramilitary Forces Act With Impunity In Spite Of Armed Forces Knowledge That They Are Mobilizing Over 1000 Men In Arauca', Nizkor International Human Rights Team, Serpaj Europe, October 3, 2001.

Though OXY has yet to announce the discovery of oil, U'wa territory -which is believed to contain nearly one billion barrels of oil -has become a dangerous battleground.

If aid to protect the Caño Limon pipeline is approved, further militarization will occur along the pipeline route. To date, rather than neutralizing armed groups, increased militarization has exacerbated armed conflict, human rights abuses and forced displacement of indigenous peoples. New aid from the United States to protest oil infrastructure will expose vulnerable peoples like the U'wa to yet greater risk.

Colombia's War is Not Our War

Disappearances and assassinations of indigenous representatives stand as tragic testimony to the vulnerability of peoples struggling to defend their territorial and cultural integrity. The assassination of five indigenous leaders, among them the founder of ONIC, during the opening of the national Indigenous Peoples of Colombia Congress in November 2001 was another reminder that in Colombia the brutality of conquest continues down the ages. The role of US military aid in intensifying that brutality is clear.

Yet despite the armed threat, indigenous peoples across Colombia continue to affirm their historical rights and voice their protest at the murder of community members. Resistance has taken many forms.

Since June 2000, the Paez peoples of the Andean mountains of southwestern Colombia have deployed 800 Paez volunteer civil guards armed only with traditional ritual batons to demand that guerillas and drug traffickers move out of their lands. Paez guards have peacefully rescued Paez children recruited by guerillas, destroyed cocaine laboratories, blockaded their roads and imposed nighttime curfews. 39

'Sticks roust rebels and drugs. Colombia's Paez Indians don't use guns but have won back their community', Juan O. Tamayo, Knight Ridder News Service, August 21, 2001.

In May 2001, indigenous peoples of Cauca joined with Afro-Colombians and small farmers to form a 20,000 strong march across the Cauca region to protest the presence of armed factions and violence against ethnic minorities. 40

'NGO Declaration Against Violence in Cauca and in Solidarity with March Against the Violence', May 17, 2001.

In June 2001, over 1000 indigenous peoples arrived in Tierralta to take part in an Indigenous Humanitarian Mission organized by ONIC to look for Kimi Pernia Domico, an internationally known Embera Katio spokesperson who was abducted by armed men on June 2. Tierralta is the breeding ground and operational base of AUC. 41

'Colombian Indians Resist an Encroaching War: Indigenous People Join To Search for Leader', Scott Wilson, Washington Post, June 18, 2001.

Though the search for Kimy Pernia was largely symbolic, Colombia's indigenous peoples succeeded in hitting home their message that Colombia's war is not their war. As Jesús María Aranda of the Cauca Indigenous Regional Council stated,

"It is simple. We only ask for what is ours".