La Gran Marcha: The Sleeping Giant Awakes

by Leslie Radford Monday, Mar. 27, 2006 at 1:08 AM | la.indymedia.org

On March 25, immigrants and their supporters shook the halls of Congress, and, just maybe, changed history.

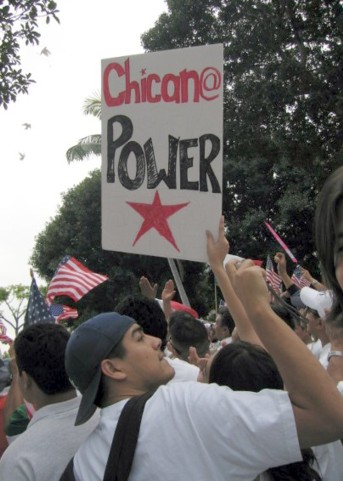

LOS ANGELES, March 26, 2006-- What happened yesterday? The Los Angeles Times estimates 500,000 people turned out; Univision estimates 2,000,000. You can read about it anywhere--a Gran Marcha against the Sensenbrenner immigration reform bill. The pictures are spectacular. Doves were released, a horn blared, a marching band played.

Those of us who couldn't get close to the speakers' platform joined semi-organized mini-marches of several thousand people, led by the SEIU, LA-ANSWER, and UNO. Waves of people standing in the streets broke into spontaneous chants of "¡Aqui estamos y no nos vamos!" And always there was, "¡Sí, Se Puede!" Outpacing the masses or going the other direction, against the tide, meant squeezing along building walls and non-stop "con permiso."

After the March, thousands of people stood in line after line along the overpasses along the 101, waving flags and celebrating. The resounding honks of car horns rising up from below us was near-deafening.

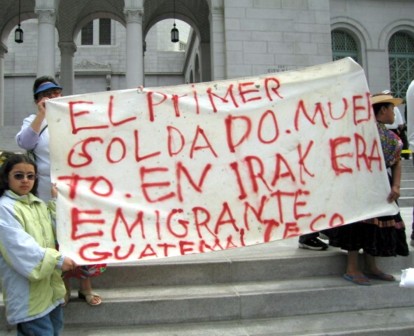

Except for a fracas between police and a few marchers at the end of the event, which resulted in no arrests, the police were nearly invisible and the protestors were resolute and calm. Firefighters were cheered wherever they appeared, and I've never seen so many U.S. flags at a protest, raised side-by-side with Mexican, Guatemalan, Honduran, and Salvadoran flags, or small U.S. flags topping the flagpoles of foreign flags. Occasionally, a U.S. flag was held upside-down, the international signal for a ship in distress.

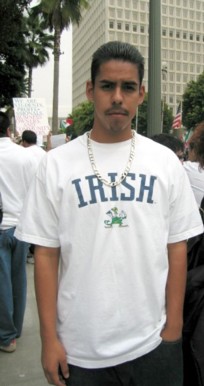

Two other protest anomalies were apparent: the sea of white shirts signaling "peace," and the families - grandparents, youth, toddlers, and the ubiquitous strollers.

I asked what the the shirts, the flags, and the families meant. Let me try to explain what I learned.

Reframing the National Debate

A March that was billed as "anti-Sensenbrenner" became, in the hands of the people, a march for legalization. In one sense, the underlying theme is not dissimilar to the argument for legalizing pot: acknowledge in the light of day what is tacitly condoned.

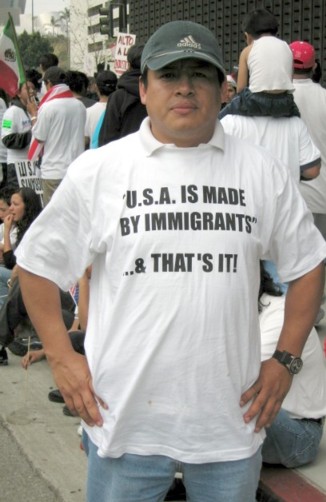

For ten thousand years and more, the people who live in what is now Mexico passed freely into what is now called the United States. Then the Europeans arrived, and the massacres began.

Sixteen decades ago, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo declared that ranchers and ranch hands, any Mexican or Native American in the new U.S. territory who wanted to keep their land and livelihood, were citizens of the United States (and would be grouped racially with European immigrants). To avoid land confiscation and with the gold rush of 1849, as many as 100,000 Mexicans opted for citizenship. Since then, the U.S. has manipulated the natural movement of peoples for its economic gain. In the 1920s, farm workers were brought in from Mexico, only to be deported in the 1930s. With 1942 Bracero program, the U.S. government and U.S. business actively encouraged the immigration of cheap labor from Mexico, welcoming workers even as they deported them during the late 1950s "Operation Wetback." The Bracero program ended in 1964. In 1984, undocumented people were offered amnesty and citizenship.

Twenty years later, NAFTA and CAFTA have propelled people off now unprofitable farms and into U.S.-owned foreign sweatshops at $5.50 per day. The only alternative is making the trip to the north and working for $50 per day. Sensenbrenner (HR 4437) and its companion bills under discussion in the Senate would end that option in a few weeks, with a vote and a penstroke.

Worse, under Sensenbrenner, border crossers would be deemed felons. Putting aside law enforcement for the moment, the vigilante minutemen are anticipating a field day, when they can initiate a citizen's arrest against anyone they "know" to be here in violation of felony laws. Undoubtedly, the minutemen watched the Gran Marcha on their TVs while they cleaned their guns and counted their ammunition.

The marchers wore white shirts to shout "no free-for-alls against immigrants," no white-instigated race war. In a word, the shirts were a call for peace, for a stable, legal working relationship with the United States. "No guerra, no racismo, no deportación," the marchers chanted.

The white T-shirts, crew shirts, blouses, and dress shirts with embroidered cuffs called for a truce based on legalization for people here and for a guest worker program; for legal recognition of what is and has been, in opposition to Sensenbrenner's and the minutemen's paramilitary effort to reshape history. Today, Mexicans, Central Americans, South Americans, other immigrant communities, and their children turned the debate into a question of how best to incorporate undocumented but often welcomed immigrants into U.S. society. It's a question that has waited decades for an answer.

Single Citizenship, Dual Flags

Especially in southern Mexico and Central America, emigrants may be leaving homes without electricity or indoor plumbing, or with dirt floors, for the relative luxury of life as a janitor, plumber's helper, or farmworker. Whole families save to send their most likely breadwinner away to the United States. Dropped off on the other side of the border, the new arrival hooks up with a friend or relative and enters the largely underground economy. If the expense of living here doesn't overwhelm him, he sends a few dollars home to help their wife and children, or maybe a younger brother, sister, or cousin, to cross.

The international myth of the American dream, for most undocumented foreign nationals who come here, means economic survival and cultural integrity, and little more. "Trabajar por un sueno no es crimen," read one sign.

In communities of undocumented people there is hope in the microeconomic opportunities here, even though, in the macroeconomic picture, the U.S. sucks their native countries dry and does the same to the migrants themselves once they cross to "El Otro Lado." Another protestor held up a sign, "If trying to survive is a crime, we're all criminals."

On the steps of city hall, the destination of the marchers, a banner fluttered: "Please Include Us in Your Dreams," it read.

Politically correct or not, this intimate plea is what it meant that the migrants carried so many US flags. It was a plea for inclusion and legalization, and against scapegoating, round ups, mass detention and mass deportation.

"Families United Should Never Be Divided"

Immigrants have spent their family's "fortune" on the hope of a better life for their children, and for the chance to improve their family's' lives back home. Obligations to aging parents and young offspring require that sons, daughters, and young parents cross the border, even if it might mean death. It is many young people's dream to come to the U.S., but the dream of Mesoamerican youth is unlike the dreams of U.S. youth to go off to college or adventure in the city. If a Guatemalan or Salvadoran or Honduran young person succeeds in the U.S., they are family heroes. The same spirit of family obligation is what propelled young Chicanos to abandon school on Friday in defense of their parents and grandparents.

The Gran Marcha was billed as a "family event." Strollers were everywhere. Three generations gripped each others' hands as they wended their way through the crowds. The shout that a child was lost brought the immense human wave to a halt and cheers when the child was found. A path opened up from mother to child. In Mexico, Central American, and South American communities, a family event means more than "quality time" with the kids or an "educational" outing.

Perhaps the most devastating impact of Sensenbrenner for its victims would be families ripped apart.

In cultures that survive because of family love, support, and obligations, Sensenbrenner and all the proposals before the Senate threatens not only immigrants' livelihood, but their safety net and the cultural hub of their lives. Under "immigration reform," families would be destroyed. Breadwinners, mothers and fathers, would spend months in prison before deportation.

Remaining family members would be abandoned in the U.S., struggling on one minimum-wage income or less. Children would be left without parents, turned over to the notorious Department of Human Services to find more distant family members or foster parents while their natural parents served out jail sentences and then tried to reunite with their children from across the border. Or, as happened in previous mass deportations, the children--mostly U.S. citizens--would be deported with their families.

The peace the migrants called for is the peace of families intact, with love and with squabbles, in a country that tacitly invited them, and peace with legal standing. It is the small peace of going to school, of work and taxes, of family meals with grandparents, children, and grandchildren uninterrupted by police banging at the door.

The Sleeping Giant

A year's work for hundreds of Los Angeles activists against the minutemen paid off yesterday. They held the door open from Baldwin Park and Garden Grove to Laguna Beach, Lake Forest, and Glendale, and the community had time to recognize the threat and to organize. Amidst the flags and the strollers were signs that read, "The 50 States Need 'Slaves' To Work" and signs that compared Sensenbrenner to Hitler, familiar themes to pro-migrant activists. And at the end of it all, the danzantes danced.

As one sign told Sensenbrenner, the Congress, and the minutemen, "You bug so much you woke up the Sleeping Giant."

On the Streets

Today, I overheard the manager of my local Sav-On talking with a stock clerk. The white guy in the dress shirt said, "Did you see the March yesterday? The news said 500,000 people were out." The African-American woman he spoke to said, "Yeah, it was something, wasn't it?" The manager added, "I didn't know there were so many of them. What do those people expect?" and continued, "I mean, I know they deserve better and all, but what happens if they pass that law? Is there going to be a riot?" His trepidation was unmistakable before he drifted away.

After a moment, I turned to her as she restocked items on the shelf and mentioned that I was at the March, and that the Spanish media reported one and a half to two million participants. She said, "I'm not surprised. The way those people have been brought in here, and now they get treated like this. And they really are doing the jobs nobody wants." She continued straightening items on the shelf as she went on, "My daughter, she's a manager. That's what we want for our children. We don't want those kind of jobs." I suggested that the Jewish persecution began much like this, and she agreed: "Yeah, that's right. I don't blame them for standing up. I wouldn't blame them if they took the streets. We did."